The new EU-US Treaty and the Intercontinental airline consolidation battle

Feb/Mar 2007

Part One: The five-year EU-US fight over "cross-border investment"

Two of the biggest issues in the industry, the new EU–US aviation Treaty and discussion of possible industry consolidation, are closely related. Both topics are a bit complex, and subject to both misconceptions and arguments designed to serve the agendas of interested parties. This article will review the issues and negotiations leading up to the preliminary Treaty agreement, and the industry merger/consolidation activity of recent months.On March 2, EU and US negotiators announced agreement on a comprehensive EU–US bilateral treaty. The long negotiating process dates back to a 2002 European Court of Justice ruling invalidating historical aviation treaties that did not grant rights equally to all EU airlines. The judicially mandated need to establish new treaties allowed the US to press for its main aeropolitical objective, the extension of "open skies" to the UK and the other three EU countries that still had bilateral restrictions on entry, pricing, airport access and code–sharing. The EU countered with demands to allow increased cross–border investment and management integration, including the ability of EU citizens to own and control US airlines. A five–year stalemate ensued with little progress on the US demand for increased access to Heathrow, or the EU demand for more increased foreign ownership of US airlines.

The US negotiating position was enhanced by having only one major objective: Chief US negotiator John Byerly described the 1977 US–UK "Bermuda II" bilateral as "one of the greatest crimes in aviation history". While there was some tension on the US side between the Heathrow "haves" (AA/UA) and "have nots" (CO/US/DL), conflict was limited since no one had an easily workable solution to Heathrow’s capacity constraints. No US carrier had any interest in owning EU airlines, and none invested any effort fighting for greater opportunities for foreigners to invest in US airlines. EU negotiators had to deal with two divergent sets of interests. The UK carriers were focused on "Fortress Heathrow", which needed to be either protected, or traded for new benefits of similar magnitude. The French and Germans had no privileges or protections at risk, but wanted to strengthen Air France and Lufthansa as global airlines. The French and Germans saw their carriers playing a leading role in global alliances, and demanded closer integration with their US partners, which could eventually include direct shareholdings and management control.

The EU’s solution was the 2003 Open Aviation Area (OAA) proposal, and its claim to "go beyond" open skies by permitting capital to flow freely anywhere in the US–EU "area" without regard to national borders. OAA encompassed both the British approach to cross–border investment (the freedom for Virgin to start a new domestic US airline, or for BA to acquire an existing one) and the French/German approach (cross–ownership and management integration between alliance partners).

The EU claimed OAA would be the catalyst to a major aeropolitical revolution, leading to the worldwide elimination of "national" barriers to airline efficiency, even though the EU was doing nothing to change the entrenched web of safety, legal and regulatory processes based on "national" airlines. The EU made a series of totally unbelievable claims about consumer benefits that would be unleashed by EU–US cross–ownership, for example that they would generate €15bn in incremental revenue (more than the combined totals of Northwest and Southwest) and 80,000 new jobs (more than the combined totals of Delta and Continental).

It is one thing to forecast lower fares due to the elimination of cartel–type pricing, or dramatic growth from major new entry or productivity breakthroughs, but the North Atlantic had enjoyed intense, open competition for 20 years, and it was ridiculous to argue that this particular market had huge efficiency/overpricing problems, and even more ridiculous to claim that cross–shareholdings or mergers would drive massive service expansions and fare cuts. Since the EU did little to create credibility or support for its approach within the US industry, critics dismissed OAA as a tactic to prevent serious negotiations over Heathrow.

A draft agreement was reached in November 2005, but the EU Council of Transport Ministers refused to ratify it after intense British lobbying, demanding further concessions on foreign ownership and management control of US airlines. Congressional action to permit the EU objective of 49% foreign ownership was politically impossible, and the DOT proposed new internal rules with more liberal guidelines for how it would interpret the statutory requirement of 75% "actual control" by US citizens. This proposal was actively opposed by the large US airline labour unions and politicians from both parties. No US carrier publicly supported the DOT approach; Continental aggressively attacked it and threatened legal challenge. The DOT, recognising that a proposal that had received almost no support under a Republican Congress was not going anywhere with the Democrats in control, withdrew the proposal last December. The Europeans sharply criticised the DOT, and claimed that "reform of American policy on control of airlines" was still the prerequisite to any future progress, and so many observers were surprised by the EU’s recent agreement to a treaty within the traditional 75% ownership/control rules.

Cross-border investment: Virgin in America

The March 2007 agreement suggests a major EU shift from the British to the French/German position. The British position meant stalemate, since there was no possibility of Congress changing the ownership and control laws, although stalemate also blocked the threat of new competition at Heathrow. Had the EU not been obligated to comply with the 2002 ECJ ruling that stalemate might have continued indefinitely. French and German interests are clearly concerned that if the British once again convince the Council of Ministers to reject the US Treaty, the ECJ will quickly invalidate the existing aviation treaties, and the US will retaliate by suspending antitrust immunity for the North Atlantic alliances. North Atlantic competition could function perfectly well without immunised alliances, but they are critical to Air France and Lufthansa’s ambitions of a central role in global aviation.Virgin’s application to start a domestic US airline quickly became central to the EU–US debates over cross–border investment. Supporters pointed to a consistent, logical pattern of Virgin–branded start–ups in different countries, and the economic illogic of blocking pro–competitive, pro–consumer investments on narrow grounds of shareholder nationality. Critics argued that while Virgin America may have made business sense five years ago, the window of opportunity for significant new US LCC market growth had passed, and it was not clear how Virgin America could make money in today’s environment. These critics argued that the entire EU demand to own and control US airlines was simply a ruse to protect Heathrow. The Virgin America application gave the British demands credibility.

On 27 December 2006, the DOT rejected Virgin America’s application for a US operating certificate. US law requires 75% of the voting interest in US airlines to be held and controlled by individual or financial entities deemed to be US citizens. The DOT found that 94% of Virgin America was held and controlled by non–US partnerships, and its show–cause order included a five–page flow chart tracking the ownership/citizenship breakdown of each investment group. Even if one believes that rules regarding crossborder airline ownership should be eliminated, there is little doubt that Virgin’s original application did not meet the statutory requirements. Virgin submitted a revised ownership plan to the DOT on 17 January that weakened some of the foreign investors control and protections, but did not appear to create the reality of a 75% US–controlled entity.

All six Legacy carriers, led by Continental, and two major employee unions filed objections to Virgin’s application. While United has advocated eliminating barriers to cross–border investments, it clearly wanted the old barriers to block Virgin’s plan to compete with United in San Francisco. Continental was determined to fight any proposal that did not provide increased access to Heathrow slots. While the opposition of these carriers and unions may have been motivated by narrow self–interest, the DOT’s decision was clearly based on the law and precedent, and there is no reason to believe that a proposal owned and controlled by US investors would have been rejected, even with Virgin brand licensing and Board participation.

Short-term impact of Treaty approval

Despite many complications, the Virgin America case illustrates the critical role of market entry to cross–border airline competition, and the ease with which traditional national ownership rules can be used to repel new entrants and any other threats to the status–quo industry structure. The Treaty clearly establishes EU–wide Open Skies, the major US negotiating objective, although the eventual impact on the US–London market is far from clear. The short–term advantage would appear to be with BA and BMI who will have full flexibility to move flights within their current slot portfolio, while competitors will have no Heathrow access unless they purchase slots in a highly inflated market. Some incumbents may have been hoping that the increased demand might provide the ideal opportunity to realise a big windfall from slot sales, but expected prices may not be compatible with profitable flights to the US. Competitive forces will eventually sort things out, but it is likely to be a slow process.

The Treaty provides tangible movement towards the EU objectives of cross–border investment and tighter alliance integration. US law limiting foreign control to 25% would be partially overridden by Treaty terms specifying that shareholdings up to 49% would not be deemed "controlling" and shareholdings above 50% would be considered on a case–by–case basis. Antitrust immunity rights would be extended to all EU carriers, with new expedited procedures for ATI approval and coordination of all antitrust oversight. EU carriers would have unlimited access to US routes from almost any country with an Open Skies Treaty, including many non- EU countries. Codesharing rights would be virtually unlimited, wet–leasing of EU aircraft will now be permitted, and franchising and joint branding programs would be not be subject to competitive review. The Treaty establishes a joint committee to arbitrate ownership and control issues, and the Europeans have been promised a specific timetable for moving to a "Second Stage" agreement on deeper cross–border investment rights.

The Treaty explicitly sanctions new grants of alliance antitrust immunity, although it is not clear whether AA–BA could expect immunity as soon as the Treaty takes effect, or whether it might be withheld pending actual developments at Heathrow. The two carriers have a huge share advantage over all other US–London carriers in an environment where (even under Open Skies) normal competitive forces will remain highly constrained.

The DOT appears to have delayed final review of Virgin’s application pending the new US–EU Treaty, but one would expect a quick final decision soon thereafter. If approved, one would expect the DOT to expedite the application, and the Treaty would clearly allow the DOT to apply much less stringent measures of foreign control.

Part Two: Update on airline consolidation activity

If the new Treaty is approved it would take effect in October. Lufthansa and Air France have been actively campaigning for Treaty approval, while British interests have launched a campaign attacking it. Opposition could also come from US unions opposed to any relaxation of the 75% ownership rule.Despite fevered discussion throughout 2006 of an inevitable trend towards consolidation, there is no longer any serious merger activity underway in the US. The events leading to the collapse of USAirways' bid to acquire Delta at the end of January are described at length in the analysis beginning on page 10. AirTran’s proposal to acquire Midwest Express has gone nowhere since October and is currently slated to expire on 11 April (see also, Briefing pages 16- 21). The world’s most rumoured merger is United–Continental, reflecting United’s Chairman Glenn Tilton’s aggressive campaign on behalf of "industry consolidation" and the relative compatibility of the two carriers' route networks. While the two carriers have held talks, there is no evidence they have ever gone beyond the informal discussions all Legacy carriers conduct periodically.

The urgent need in the US market is for further restructuring of hopelessly unprofitable capacity. Last year’s strong profit improvement was almost entirely driven by unit revenue gains resulting from bankruptcy–related capacity cuts. However, the industry is still not at a point where it can earn profits over a full business cycle and more cuts are still needed.

Many of those quoted in the press as favouring "more consolidation", such as USAirways' CEO Doug Parker, and former Continental Chairman Gordon Bethune, are in fact advocating "more restructuring". Parker’s bid to acquire Delta out of bankruptcy, like his earlier merger between America West and USAirways, were fundamentally restructuring exercises, not mergers.

The economics were entirely based on capacity and cost cuts that are only possible during a court administered bankruptcy process. There were some scale economies and network synergies, but these alone could not have justified the merger implementation costs and risks. Parker believed that Delta management’s reorganisation plans were inadequate, and that a more aggressive plan would provide stronger returns for Delta’s creditors as well as profit/growth opportunities for USAirways. No one has proposed a merger to take Northwest out of bankruptcy because Northwest’s standalone plans have already included extremely aggressive cost and capacity restructuring.

Mergers that may be good for shareholders (and restructurings that may be good for creditors) may threaten employees, managers and politicians fearful of losing local service. The failure of DL/US illustrates that merger/restructuring implementation is very difficult and easily sabotaged; the employment/service guarantees (and big management buyouts) needed to keep everyone happy can easily wipe out the benefits that the shareholders were hoping to achieve. Those expecting a wave of merger activity have clearly underestimated the non–economic barriers protecting $1 arrangements.

AirTran’s bid for Midwest Express reflects the unique situation of those two companies and has no broader implications for industry restructuring or consolidation. America’s "LCC" sector has found profits squeezed on the one hand by oil prices and a shrinking cost advantage versus those network carriers that have aggressively restructured, and growth opportunities squeezed on the other hand by unprofitable capacity still operated by the network carriers that have been slow to restructure. AirTran has more aircraft (737–700s) being delivered in the short term than it can profitably deploy in its current network. In bidding to acquire Midwest Express, AirTran argued it could immediately use those aircraft to replace Midwest’s older MD–80s, achieve cost savings by integrating the two carriers' 717 fleets (87 and 25 respectively), and also diversify and improve the two networks. Midwest’s Board and management clearly wish to remain independent and claimed that AirTran’s $345m offer "significantly undervalues" the airline. They have refused to either discuss the possibility of merger with AirTran, or to publicly explain why their shareholders will be better off by refusing AirTran’s offer.

AirTran–Midwest is a classic example of a "synergy/efficiency" merger, and in fact would be easier to implement than most. Mergers between larger airlines would face much greater obstacles, including incompatible IT systems, union jurisdictional conflicts, cross–border complications, or antitrust/political issues. The synergies and efficiencies are real, but much, much smaller than one would find in quasi–restructuring cases. As with DL–US, incumbent managers and employees have substantial ability to protect the $1. If the economic benefits from mergers aren’t high enough to justify huge takeover premiums and the payoffs to incumbents, then mergers won’t happen very often. The argument that cost savings and network synergies could drive a major trend towards industry consolidation just doesn’t hold water.

No general trend towards consolidation

Continental has never indicated the slightest interest in acquiring United, and one presumes that it would take an enormous premium over their current $4bn market capitalisation to get Continental to take a United bid seriously. A merger would force both carriers to reopen their union and supplier agreements, and would face implementation risks exponentially greater than cases like AirTran–Midwest or USAirways- America West. Using traditional capital market criteria, United would need to (at a minimum) double the value of Continental’s assets in order to justify the financial risk. The two route networks would mesh well, but linking them would not create $4bn in new corporate value. Continental, Delta and Northwest, who also have compatible networks, have explored a variety of merger scenarios over the past decade, but have never come up with an economic justification for moving forward.Despite the steady drumbeat of press coverage of industry consolidation, there has never been any justification for the claim that the worldwide aviation will inevitable move towards fewer, bigger airlines. A previous analysis (see Airline Consolidation: Myth and Reality, Aviation Strategy, November 2006) discussed the underlying economics and argued that while mergers make good sense under certain conditions (such as restructuring cases), they are inherently very risky, and have an extremely poor historical track record. The US merger boom of the late 1980s, was a dismal failure, and did nothing to improve the overall efficiency of the industry. There is no evidence that industry consolidation is underway, and most sectors have been steadily expanding. There is no reason to expect any "natural" trend towards consolidation since aviation is not a mature industry with declining demand or stagnant technology.

Qantas - betting $8bn on an aeropolitical revolution?

Recent activity illustrates that the scale economies and network scope efficiencies used to justify most mergers are much too small to justify a general trend towards consolidation, and that there are still huge non–economic barriers to mergers and restructuring efforts that make a general trend even less probable. The importance of scale and scope has been steadily declining; most of the industry trends of recent years (simplified LCC business models, internet distribution, new IT technologies, improved supplier/ outsourcing capabilities, alliances) have made it much easier for smaller airlines to compete profitably. In December, Qantas' Board accepted an $8.7bn (A$11.1bn, €6.7bn) takeover offer from an investment group led by two Australian groups (Allco Equity Partners and Macquarie Bank), and two overseas groups (Texas Pacific (US–based) and Onex (Canadian). The offer represented a 33% premium over Qantas' previous share price, and will be financed by A$3.5bn from the equity partners, and A$10.6bn borrowed from a consortium of banks. The investor group said they fully supported Qantas' current strategy and management team and promised "business as usual". In contrast to the transaction- based wealth being amassed by the top executives at the bankrupt US carriers, CEO Geoff Dixon pledged all earnings from the new owners' management incentive scheme to local charities.

To meet national ownership rules (which in Australia allow a 49% foreign shareholding), the new owners were forced to establish a complex governance structure. Allco, which provided 35% of the equity, will get 46% of the voting shares, while US–based Texas Pacific will get only 15% of the voting shares despite contributing 25% of the financing. The foreign investment quickly raised political hackles, even among "pro–business" conservatives. The government could have blocked the acquisition on "national interest" grounds and withheld approval until the new shareholder promised that headquarters and management/technical staff would remain on Australian soil.

Prior to the unexpected takeover bid, Qantas was valued at $5.5bn. If the new owners refloat or sell Qantas in three years they would need to realise roughly $15bn to justify the risk of their investment. Qantas is widely perceived to be well managed, thus it seems unlikely that huge profit improvements will come from asset, marketing or operating opportunities that current management had somehow missed. It would be dangerous to assume that Qantas' recent earnings growth (largely due to reduced/stabilised competition in its key US, UK and domestic markets) can be easily extrapolated into the future. In January Qantas announced that it would take a minority stake in Pacific Airlines, a small Vietnamese operator, but investments of this type are very risky, and are not likely to be the foundation of Qantas' growth strategy.

It is implausible that the new owners actually expect that a "business as usual" approach will produce strong returns on their $8.7bn. It appears that this is (at least in part) a wager on future consolidation among the large Intercon airlines, and the Texas Pacific/Onex investment would appear to be a perfect example of the cross–border capital movement that Glenn Tilton has been advocating. Under this theory, shareholders could enjoy a huge windfall if governments decide to change the rules restricting cross–border ownership and operations, especially if the airline (like Qantas) has a strong brand and network franchise. Opportunities might arise to either profitably acquire weaker franchises or to sell out to someone building a true global airline. But it is not clear why one would expect the required aeropolitical revolution to occur anytime soon, or to produce conditions favourable to Qantas. There is absolutely no public or political support for cross–border consolidation, and the knee–jerk political response to Qantas' new shareholdings illustrates how easy it is to mobilise a campaign against any threatening "foreign" deals.

Under the status–quo aeropolitical system, international airlines are blocked from certain types of cross–border investments, growth opportunities and mergers, but as highly visible "national champions" also benefit from many special advantages. Canberra has protected Qantas many times in the past, for example reneging on an open skies Treaty with New Zealand, thwarting Singapore Airlines efforts to invest in the domestic market or to serve the Australia–US route, and strictly limiting the capacity growth of Emirates and other new longhaul competitors. If one weakens or eliminates the "flag airline" concept, Australian politicians become much more receptive to the lower fares that SQ/EK–type competition would bring, and these points were raised by local politicians in response to the Texas Pacific/Onex foreign investment. If Qantas invests in airlines competing with the flag airlines in Singapore and Vietnam, it is difficult to block foreigners from doing the same in Australia, and in early February, Tiger Airways (49% owned by SIA) announced its desire to obtain an Australian operating licence in order to challenge the Qantas–Virgin Blue domestic duopoly. If Qantas pursues "global airline" mergers, landing rights in countries like Japan and India are put at risk, and Australia’s leverage over carriers like Emirates is lost.

The Qantas/United approach appears based on hope that governments will grant their shareholders new freedom to pursue advantageous cross–border transactions while fully maintaining all of the entry barriers and special advantages that "national champions" have always enjoyed. Such a shift in government policy could create an enormous windfall for current shareholders, since capital markets would quickly appreciate the value of mergers between highly protected companies. But if these aeropolitical shifts do not occur, Qantas' new owners will need to return to the question of how to triple the value of the company within a "business as usual" environment.

Part Three: Intercon merger and consolidation politics

Intercon competition realities The competitive dynamics of the Intercon and "non–Intercon" sectors are totally different and it would be dangerous to consider Intercon competition by the same standards as most domestic and regional airlines. Most short-/medium haul, narrowbody airline markets around the world are highly liberal and enjoy healthy competition, even though many operations cross national borders. Safety and economic regulation only involves dealing with local governments or a limited set of bilaterals with neighbouring countries. In a simple, familiar environment, governments are more comfortable letting "market forces" dictate airline competition. Carriers can react more quickly to demand and competitive changes.

Intercon airlines do not operate in a liberal environment; airlines viewed as "national champions" get special protections, badly run airlines are subsidised, and there are huge barriers to new entry. There are many countries that have liberalised market entry and competition in domestic/regional markets while maintaining rigid restrictions on longhaul competition (Malaysia and India for example). Even though some markets (the North Atlantic) are liberal, Intercon airlines cannot invest or organise across borders without jeopardising access to the many markets (India, Japan) that are not. In this highly multilateral environment, governments remain fearful that other governments will distort airline competition to favour their carriers, so all of them maintain close control over market entry and route rights.

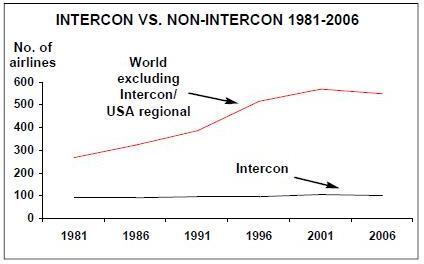

As the graph below demonstrates, the highly competitive non–Intercon sector has demonstrated dynamic growth over the past 25 years, while entry/exit barriers have left the Intercon sector totally stagnant. Non–Intercon growth results from a steady "dynamic churn" of airlines; half of the nearly 1200 carriers in this sector exited the market after merger or failure, allowing stronger carriers to grow and new carriers to enter. In a dynamic environment like this mergers have nothing to do with "consolidation", and in fact are key to driving growth. Intercon market entry has been extremely rare in the past, and remains extraordinarily difficult. Market exit is only small fraction of the non- Intercon rate, and virtually nonexistent outside America and northern Europe.

Efficient airline competition requires four conditions to hold:

- Large enough markets to support a reasonable set of competitors (each large enough to achieve efficient operating scale)

- Efficient capital market process that will reward profitable airlines and punish weak ones (shifting capital to where it can earn the highest returns)

- No artificial barriers to market entry and exit

- Full marketing freedoms (pricing, scheduling, product, branding)

No airline markets are perfect, but most non–Intercon markets fulfil all four conditions to some degree. Intercon markets are highly deficient; some markets are large, and pricing freedom generally exists, but there are huge barriers to entry, exit, and the efficient allocation of capital.

The drive for oligopoly on the North Atlantic

The markets with the best market conditions are obviously the US and the EU, with very liberal conditions in markets large enough to support substantial competition, and efficient capital market processes. When markets support multiple competitors, governments can focus on the interests of consumers and market efficiencies, when there is a dominant national carrier, governments are highly susceptible to lobbying to distort competition on its behalf. The worst competitive conditions are the Intercon market, and very small/developing country markets, too small to support competitive airlines at an efficient scale. It is perfectly fair to argue that the aeropolitical system of "national airlines" creates inefficiently small airlines in certain parts of the world, but it is silly to argue that because of this system Lufthansa and United are inefficient and uncompetitive. Cross–border barriers to capital may create serious distortions and inefficiencies in Peru or Vietnam or Jordan, but there is no evidence of serious distortions in America or Europe.The North Atlantic, one of the world’s biggest Intercon markets is really two markets- Continental Europe (72% of the total traffic) and the UK/Ireland (28%, dominated by the huge London market). Continental European O&Ds are served by hubs on both sides of the Atlantic (including London), but the European carriers and hubs do not compete for London/Dublin traffic. The divergent US Treaty objectives of the British and French/Germans reflected this market split. Only one–third of the continental market is in O&Ds with nonstop service, while three–quarters of the UK/Ireland demand is in nonstop markets. It is impossible to compete without hubs and alliances on the continent, while the UK/Ireland markets are much more vulnerable under "open" market conditions.

The original alliances of the 90s (KL–NW, DLSR- SN and UA–LH) created tangible consumer benefits within a highly competitive environment. Successful carriers (CO, KL) entered and expanded at the expense of weaker carriers (TW, SN), and the overall market was strongly profitable. But the EU shifted course, first allowing Lufthansa to eliminate competition with airlines from most neighbouring countries (SK, OS, LO, LX, TP, TK), and then allowing Air France to acquire KLM, dramatically reducing longhaul competition. The Air France–KLM merger reduced the number of viable Continental alliance competitors from three to two, and the overall set of major competitors from five to four (counting Continental and BA connections via London). It also forced merger discussions between US carriers, since either Delta or Northwest will eventually lose the alliance capability they had since the early 90s.

Having facilitated a doubling of North Atlantic concentration between 1999 and 2006, the EU has spent the last two years fighting to make it possible for Lufthansa and Air France to exert much tighter control and (perhaps eventually) own their US partners. Lufthansa and United have virtually unlimited freedom to work together on schedules and pricing today; the only purpose of "increased antitrust immunity" and cross–shareholdings would be to eliminate any remaining tendencies to compete independently. The Treaty also appears to pave the way for antitrust immunity between BA and AA, which would give them overwhelming dominance over the next largest competitors in the US–Heathrow and the overall US–UK market.

The 2009 table column (see table, right) assumes events widely discussed in the context of "industry consolidation"-a United–Continental merger, an immunised AA–BA alliance, and that Iberia and Alitalia cease to function as independent competitors (through merger or joining an alliance). While different scenarios are possible, it is easy to see how the Continental Europe market could quickly become a 90% two–carrier oligopoly and the US–UK market could be dominated by one alliance with a 60+% share. A United–Continental merger makes no sense if one looks at scale economies or network synergies within the USA, but makes perfect sense in the context of a plan to give Star the dominant position within this 90% oligopoly. There is no way to explain Air France paying a 40% premium for KLM under the market conditions of 2004, especially given barriers to staff reductions, fleet simplification and overhead reduction. But if one views the purchase as elimination of competition and a decisive move towards this permanent oligopoly, then Air France made a wise purchase.

No single policy/aeropolitical change (transatlantic antitrust immunity, intra–European alliances, the AF/KL merger, increased EU–US cross–ownership, etc) was decisive in the shift from competition to oligopoly, but the combined effect of all of these changes has been overwhelming. The move from 20–30% concentration to 40–50%, or even 60% concentration posed few risks to consumers, and some of this was the inevitable winnowing of marginal competitors. Each isolated move was defended on the grounds that there were still many forces in the market that could constrain any anti–competitive behaviour. But one by one, each of those forces have been eliminated.

Intercon consolidation and antitrust policy

The shift from 30–50% concentration to 80- 90% concentration can be regarded as strictly the result of government intervention at the behest of large airlines (merger approvals, the EU–US Treaty negotiations) and not the result of "market forces". It should also be emphasised that this governmentally engineered move towards oligopoly did not occur in a struggling, declining market, but in an already strongly profitable market experiencing robust demand growth. It occurred in a market where there has been no meaningful market entry in decades, and where barriers to new competition (including airport capacity constraints) keep getting stronger.A profitable market that has always had major entry barriers and competitive constraints cannot become highly concentrated unless antitrust rules are waived or manipulated. Major inconsistencies between the EU’s treatment of the Air France–KLM and Ryanair–Aer Lingus cases appear linked to the EU’s active support for Intercon consolidation.

In October, Ryanair put forward an all–cash €1.5bn ($2bn) offer to acquire Aer Lingus. Ryanair has generated the strongest returns of any European airline over the last decade, and argued that it could significantly increase returns on Aer Lingus' assets. This would be a challenging merger, given the widely divergent business models and corporate cultures, and press reports suggested that Ryanair was nowhere close to getting sufficient shares tendered to complete the acquisition. But on 21 December Ryanair was forced to withdraw the offer when the European Commission said it would need five months to determine whether the acquisition would create an irremediable violation of antitrust law. The issue here is whether antitrust law required government intervention to block the normal workings of the capital markets, and why such a review should require five months.

64% of all European airline revenue is longhaul while only 36% is for travel within Europe, or to North Africa or the Middle East. Half of this enormous long haul market is destined for smaller European airports (Tokyo–Lyon, Johannesburg–Hamburg) which cannot be served except via a European connecting hub, and where competition is strictly limited to European airlines. Most foreign airlines are not independent competitors due to restrictive bilaterals and revenue sharing alliances.

The view of the European Commission appears to be that this segment (32% of the entire European market) can be fully served by three dominant European companies, with no possibility of other competition, while another 32% of the market (traffic destined to the large hub gateway cities) can be fully served by these same three companies supplemented by open, independent competition in a few isolated cases. When Air France acquired KLM, shrinking the number of large competitors from four to three, the European Commission focused almost exclusively on the trivial number of overlapping nonstop O&Ds. This ignored both the magnitude of the longhaul connecting business, and the very concept of airlines as a network business. The Commission required less than a month to determine that an Air France–KLM merger created no serious antitrust problems, even though there is absolutely no possibility that new Intercon market entry could correct anti–competitive behaviour in the future.

The Irish markets served by Ryanair and Aer Lingus account for less than 1% of total European airline revenue. There are no bilateral type entry barriers, there is a huge set of active competitors, and there is no service overlap between FR and EI at any slot constrained airport. While protections for future entry at Dublin would be appropriate, the combined FR–EI share at Dublin is no greater than Air France’s share at CDG.

There is no defensible antitrust standard that would wave through KLM–Air France but raise serious red flags about Ryanair–Aer Lingus. Nor does it seem consistent that EU policy permits mergers to create a dominant national carrier in France, Britain, Italy, Spain, Sweden, Belgium and Holland, but object to the same thing in Ireland. The European Commission may discover simple remedies for whatever Irish market issues its exhaustive review may identify, but the incoherency of its overall approach raises the troubling prospect of one set of antitrust rules for "national champions" and a completely different set of rules for everybody else.

The risks of Intercon consolidation

Intercon oligopoly would be impossible under Aer Lingus–type antitrust standards. The Air France–KLM merger might have won approval, but only under conditions protecting overall levels of longhaul competition, such as reduced sanction for alliance price and schedule collusion. The EU’s airpolitical negotiations are clearly serving to facilitate high levels of Intercon consolidation; antitrust administration appears to serving that policy objective as well.Advocates of Intercon consolidation quoted in the press have attempted to portray their efforts as a minor adjunct to a general worldwide trend towards consolidation, a trend that isn’t occurring. This conflation of the economics of a handful of the largest Intercon carriers with the hundreds of non–Intercon airlines creates a variety of false impressions:

- Consolidation may be a natural trend that many industries go though (there are "too many airlines" so no problem if United merges with Continental or Lufthansa),

- Consolidation will force needed restructuring (even though mergers do nothing to fix bankrupt carriers like Alitalia or Northwest),

- Consolidation is being driven by powerful synergies or efficiencies (arguing that United or Lufthansa lack efficient scale presupposes that the ideal airline was the Aerflot of the 1980s)

- Consolidation doesn’t threaten consumers because there is plenty of competition (everywhere except Intercon markets which have never had market entry/exit, and remain hugely distorted by government interference and other barriers)

Intercon consolidation advocates have falsely claimed they their objective is to do away with the 60–year old system of "national airlines". Airlines, it is argued, should be free to organise themselves anyway they want, just like any other consumer product company. Headquarters could move to Singapore, maintenance could move to China. Whatever the academic merits of such an argument, all safety, financial, consumer and workplace regulation of airlines is based on the traditional "national airline" system, these systems are highly entrenched; nobody is actually doing anything to create new regulatory schemes to replace them, and it would be a huge undertaking even if the political will existed (which it doesn't). The EU has had major problems aligning safety regulations within the EU.

The Open Aviation Area as originally proposed would have done nothing to change the traditional aeropolitical system, and the new Treaty merely replaces Dutch and Belgian nationalities with an "EU community" nationality under the traditional system, just as Norway, Denmark and Sweden established a joint nationality in the late 1940s. The major benefits of true "trans–national" airline deregulation would be in small countries, with inefficiently small airlines and markets and many illiberal restrictions, yet 100% of the recent discussion has focused on the US and the EU.

The Intercon consolidation movement does not reduce government interference with airline competition, and actually depends on maintaining it. Excessive Intercon concentration creates short–term market distortions and the risk of undermining longer–term innovation.

| Market Concentration | 1989 | 1999 | 2006 | 2009 (?) |

| No. of airlines with >1% share | 27 | 20 | 10 | 6 |

| Top two airlines' share | ||||

| Total North Atlantic | 20% | 24% | 57% | 72% |

| Continental Europe | 30% | 65% | 87% | |

| (72% of total N. Atlantic) |