Swissair - will tough ROIC target be met?

February 1998

Swissair, the airline, will return to profit in 1997 after posting a loss (on flight operations) in 1996. But despite major strategic changes over the last two years, the future for an airline that has a high cost base, a non-EU location and, critically, which can now be compared directly with other Swissair group divisions, is far from certain. Swissair faces the classic problem of mid-sized European airlines — it is not big enough to be considered one of Europe’s big players, and it is not small enough to settle for the role of a niche carrier. Substantial changes have been made by the airline and the group’s management (Jeffrey Katz is CEO of the airline and Philippe Bruggisser is group CEO) — but will these be enough to solve the fundamental problems that Swissair now faces?

Corporate reshuffling

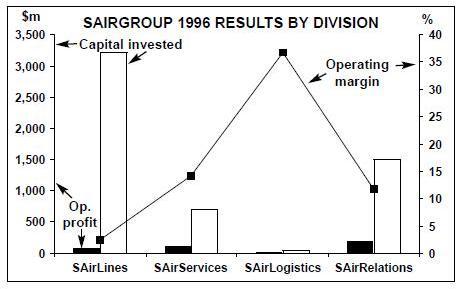

Among the key changes has been the creation of the SAirGroup in 1996, which comprises four strategic divisions: SAirLines (including Swissair, Crossair and Charter Leisure), SAirServices (maintenance, airport services and IT), SAirLogistics (cargo and logistics) and SAirRelations (catering, hotel management and duty-free). Each division is supposed to be autonomous, responsible for its own bottom-line result and developing its own business strategies under its own brand(s). However, the “Swissair Experience” — defined as all the activities traditionally associated with Swissair — extends throughout the four divisions. So does the company operate truly independent divisions, or do divisional decisions depend on their effect on the “Swissair Experience”?

This is more than just a theoretical question the ways in which the divisions interact are a key determinant in how Swissair (the airline) is able to carry out its chosen strategy. If the divisions are to attract — and justify a return on — outside capital on an individual basis, then transparent, accurate divisional results are a necessity. According to Katz, divisions “must pay due regard to the overall interest of the Group as a whole”. With regards to inter-group trading, Katz adds that divisions offer services at general market rates and that “as a general rule” these rates should be applied to intra-group business. So far so good, but Katz also claims that “companies are expected to make use of their sister companies’ services wherever possible, provided they are offered at competitive market rates”. The problem is twofold: just how is the “going” market rate defined (and by whom) and, despite group guidelines, what kind of unofficial pressure do managers feel to buy intra-group services? If Swissair is truly going down the road of divisional autonomy then only one rule must apply — the rule of the market.

Alliances everywhere

Within Europe, Swissair’s alliance strategy is determined by Switzerland’s location outside the EU. Until that changes, or until an EU-Swiss transport deal is finally agreed, Swissair can only gain access to EU markets via alliance deals. The most recent was with TAP. Long term, a 10% stake in a privatised TAP (expected in 1999) is a possibility, but short term improved SwissPortuguese passenger flows are the main gain. Signing alliances in all the main EU markets is a painstaking process, particularly as flag carriers have other priorities and larger airports have little spare capacity, leaving second-tier airlines or start-ups based at secondary airports as Swissair’s best option. Hence Swissair has been talking to, among others, AOM and Air One (the latter after having being rebuffed by Alitalia, which chose KLM as its main European partner rather than Swissair or Air France — see page 13).

As marginal as some of the increased traffic flows resulting from alliances with smaller European airlines may seem, Swissair has little alternative. At least the airline should not repeat the experience of Sabena, in which its 49.5% stake has been written-down. Swissair, however, does claim that the Sabena link has generated “substantial savings” in a number of areas, and that further constructive collaboration is possible.

While the EU market remains problematical, long-haul alliances become vital to Swissair. Katz says: “A key goal is to maintain our status as the preferred carrier in Europe for long-haul travel.” Swissair’s Atlantic strategy largely depends on Atlantic Excellence, which combines Delta Airlines, Austrian Airlines, Sabena and, soon, TAP Air Portugal, but Delta also has a rather distracting agreement (from Swissair’s point of view) with Air France — and this relationship has yet to be fully developed. And can a Swissair/Delta alliance ever be as beneficial as Lufthansa/United, KLM/NWA or BA/American? Geography says no — Zurich is not as attractive a step into Europe for the North American market as is Amsterdam, Frankfurt or London, and Switzerland compares badly with other European countries in terms of O&D traffic. Switzerland ranks seventh in Europe in terms of international scheduled passengers, and Zurich has less international transfer traffic than Frankfurt, London Heathrow, Schiphol and Copenhagen.

At first sight, however, results from Atlantic Excellence, which was granted anti-trust immunity by the US DoJ in June 1996, have been impressive — over the first eight months of the alliance (February-September 1997) ASKs among the Atlantic Alliance partners across the North Atlantic rose by 10%, and RPKs by 20%, with load factor rising six points to 79%. Yet both Delta and Swissair have been cutting fares to the US, so an increase in passengers flown may not have too great an effect on the bottom line. And the split in benefits of the Atlantic Alliance between Delta and Swissair is not known. It does make sense for Swissair to ally with a major US airline — but how crucial is the link with Swissair to Delta?

Until the end of 1997, Swissair’s Asia links depended largely on Global Excellence — the link between Singapore Airlines, Swissair and Delta that dated back to 1989. Now that Singapore has withdrawn from the accord, Swissair has decided not to seek a direct single-partner replacement but to concentrate on signing individual agreements with Asian airlines for specific routes. The Asia/Pacific market is vital to Swissair. According to estimates by UBS, Asia/Pacific traffic revenue accounted for 19% of total Swissair traffic revenue in 1996; that exposure is greater than Lufthansa (18%) and British Airways (16%), and only just behind KLM (21%). Existing codeshare deals with carriers such as Malaysia Airlines will be followed by others in 1998, and Swissair is talking to airlines in south-east Asia, Japan and China.

Alliance activity will therefore take up a fair proportion of management time at Swissair this year and, according to Katz, Swissair realises that it cannot survive long term without “being part of a larger system”. But as Katz adds, “Without core profitability, alliances do not matter” — and that is at the heart of the challenge that Swissair faces.

Profits, costs and yields

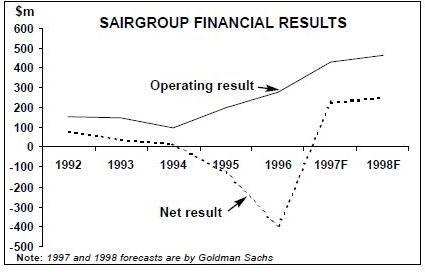

The company has posted a ragbag of results over the last few years (see graph, above). The airline division’s weak 1996 results were due partly to rising fuel prices, the strong Swiss franc, reorganisation costs and, alarmingly, to yield erosion. Despite a 5% decrease in airline unit costs in 1996, lower fares and an adverse change in the traffic mix led to a 6.5% reduction in yields. The fall in unit costs (a similar fall to 1996 is expected for 1997) stems from concerted cost-cutting over the last two years. Labour costs have been a high priority, and measures have included revision of collective working agreements, the switching of some pay to profit-related bonuses, and voluntary redundancy or early retirement for 1,200 staff through mid-1996 to mid-1997. The airline also introduced foreign (i.e. cheaper) flight attendants on some long-haul routes in 1997, and the group employs up to 14,000 part-time workers.

Costs have also been reduced via new scheduling, seat configurations, product innovation, yield management systems and fleet harmonisation. Swissair has gradually switched from a McDonnell Douglas-dominated fleet to an Airbus-dominated one (see table, page 14). European operations are now flown entirely by A320 family aircraft, which replaced MD-81s and A310-200s over a three-year period. A330-200s and A340-600s will form the core of the long-haul fleet, although MD-11s will remain until 2002-2006. The average age of the Swissair fleet is now less than 5 years.

Other measures included, from autumn of 1996, the switching of long-haul departures from Geneva (where they made a loss) to Zurich. There is now a Geneva-Zurich shuttle, and the switch has stimulated long-haul demand. However, there may be a costly side-effect — new entrant carriers may target Geneva. Yet Zurich does have more transfer opportunities than Geneva, and this has helped Swissair to improve its load factor (68% in the first six months of 1997, compared with 62% in 1996, and which may reach close to 70% for the whole of 1997). In addition, Crossair, SAirLines’ regional airline, has been growing fast, taking over many short-haul charter and scheduled services; and long-haul charter operations have been regrouped under the Balair/CTA Leisure brand, renamed Charter Leisure from autumn 1997.

The end result is that airline unit costs will have declined by double figures over 1995-97, but the problem for Swissair is that if, like other European airlines, it cannot slow the pace of yield erosion, further cost-cutting will be needed — and cost-cutting opportunities are not limitless for an airline based in Switzerland. Selling and distribution must be the next target, to be accompanied by attempts to increase productivity and even outsourcing.

The future

The write-down of the Sabena stake and other provisions means that the 1996 result is an unfair basis on which to judge the company. The 1996 figures were also calculated according to International Accounting Standards for the first time, so historical comparisons are not particularly valid. The 1997 half-year results were encouraging, and were helped by economic upturn in Switzerland and Europe. Swissair’s load factor rose from 62% to 68% for January-June 1997. But it is the 1997 results that will reveal just how effective the measures adopted by management have been. The group will return to net profit in 1997, and Goldman Sachs estimates a turnover of $6.6bn, operating profit of $428m and net profit of $225m. UBS estimates an operating profit of $408m and Aviation Strategy’s estimate for operating profit is $420-430m. The 1997 results will be helped by lower fuel prices (jet kerosene has fallen by $100 per tonne since the high of October 1996) and the weaker Swiss franc (in 1996 $1=1.24Sfr; in 1997 $1=1.46Sfr). Indeed, some analysts believe that the group’s stock has a correlation with the strength of the Swiss franc. If the currency becomes stronger in 1998, it will affect the bottom line.

However, the airline’s contribution to group results is less certain, and comparisons between the divisions will be revealing. According to Swissair, the rationale behind the changes adopted in 1996 was to improve return on invested capital (ROIC) from the 5% the group achieved in 1995 to a target of 12%. In 1996 ROIC improved to 6.3%, but in the first-half of 1997 the return fell to 4.7%, and there were wide differences between the divisions (see table, left, and graph, right). According to Katz, SAirLines has a target ROIC of 8%, but the division did not improve ROIC at all in the first half of 1997. It is unlikely that it will catch up with the ratios of its fellow divisions for the whole of 1997. SAirLines’ failure to increase ROIC comes despite all the cost-cutting and changes that have occurred over the last two years. And if the airline division cannot achieve a better ROIC now, what will happen when the next aviation recession arrives, particularly as continuing fleet renewal will be capital intensive? What more can the airline do? EU membership for Switzerland or an EU/Swiss airline accord would be a major boost for European traffic, but Swissair cannot change geography and the alliance with Delta may not last long term.

Some analysts are getting concerned. In mid January Swiss Bank Corp. cut its recommendation for Swissair from buy to hold. Therefore over and above the current cost-cutting measures, the airline may need some radical thinking from management. While Crossair specialises in lowcapacity, short-haul routes at present, why not expand its activities to jets and let it serve all existing Swissair European routes, leaving Swissair to fly long-haul only? Or how about exploiting more fully the Swissair brand, which Katz describes as a “killer brand”. The airline could consider reverse outsourcing, via the use of Swissair as a branding for First or Business Class throughout the Atlantic Excellence alliance — i.e. even on non-Swissair flights. This would be a logical extension of Swissair’s goal of being the preferred carrier in Europe for long-haul travel, and true alliance management means subjugating airlines, and their brands, to the needs of the alliance as a whole.

Yet the brand can only be exploited if it remains strong. Bruggisser says: “Swissair has a high-price image ... we must work on that perception.” That may be a mistake — even if service standards remain the same, reducing fares runs the danger of altering customers’ expectations. The link between price, quality and brand is a complex one, and reducing fares may improve revenues short term at the cost of reducing Swissair’s ability to exploit its brand long term.

Without innovation, the airline will struggle to meet the returns on capital the other divisions are now delivering, and it will be trapped in a cycle of managing yield decline and adopting cost-cutting programmes until costs can be cut no further. Although SAirGroup may disagree, the message to an impartial investor from the divisional results is clear: develop other revenue streams wherever possible (and not necessarily airline-related activities). For example, Swissport International, part of SAirServices, now has ground handling contracts everywhere from Puerto Rico and Brazil to Kenya and Egypt, while SAirRelations is acquiring European airport restaurants. At the very least SAirGroup cannot afford to sell off profitable non-airline assets in order to release further capital for the airline.

The airline and the group face a dilemma. If SAirLines follows the “Swissair Experience” maxim too rigidly, there may be danger of mirroring SAS’s “Total Travel” concept. What should link Swissair’s divisions should not be the serving of a single customer’s interest — i.e. the airline passenger. That is because — as SAS found out to its cost — other companies can better provide parts of the travel experience than Swissair can. Instead, SAirGroup’s divisions should uniquely serve the interests of the customer in their particular market, whether it is hotels, catering etc. Only when the divisions are leaders in their own markets in their own right should links across divisions be exploited.

At present, an impartial investor could even make a case for the group selling off the airline division, as it is still the poorest performer. Of course SAirGroup will never do that, as most of the other divisions depend on the Swissair airline branding. Yet a brand is an asset in its own right and does not necessarily need further assets (such as aircraft) behind it. But perhaps that is too radical a step for any airline at present, let alone Swissair.

Given the “Swissair Experience” doctrine, SAirGroup still sees itself as an airline-dominated group. If it wants to stay that way, the results of SAirLines — and in particular Swissair airline must be drastically improved. And that means Jeff Katz or someone must introduce radical changes and shake up the Swiss-dominated management thinking. Playing safe may no longer be an option for Swissair if it wants to remain an important airline in Europe.

| Current | Orders | Delivery/retirement schedule | |

| Long-haul | fleet | (options) | |

| 747-357 | 5 | - | To be retired from winter 1998/99 |

| A310-300 | 8 | - | To be retired from winter 1998/99 |

| A330-200 | 0 | 15 (10) | 9 from Oct. 1998 onwards; 6 from |

| MD-11 | 4Q 1999 onwards | ||

| 16 | - | Four to be bought from LTU from Nov. | |

| 1998 onwards; all 20 MD-11s to be sold | |||

| A340-600 | to “a US carrier” during 2002-2006 | ||

| 0 | 9 (10) | Delivery from 2002 onwards | |

| Short-haul | |||

| A319 | 8 | - | |

| A320 | 18 | 1 | Delivery in summer 1998 |

| A321 | 8 | 1 | Delivery in summer 1998 |

| TOTAL | 63 | 26 (20) |

| Revenue Operating Operating | Op. return | Operating | |||

| profit | margin | on invested | profit per | ||

| SAirLines | capital | employee | |||

| $1,787m | $62m | 3.5% | 2.7% | $6,100 | |

| SAirServices | $606m | $49m | 8.1% | 8.2% | $7,600 |

| SAir Logistics | $385m | $19m | 4.9% | 84.8% | $10,200 |

| SAirRelations | $1,122m | $43m | 3.8% | 4.1% | $2,400 |